In Nobody Is Talking About This, Patricia Lockwood writes about impressionability in a way that still makes me wince in recognition: “Back in 1999, she had watched five episodes of The Sopranos and immediately wanted to be involved in organized crime. Not the shooting part, the part where they all sat around in restaurants.”

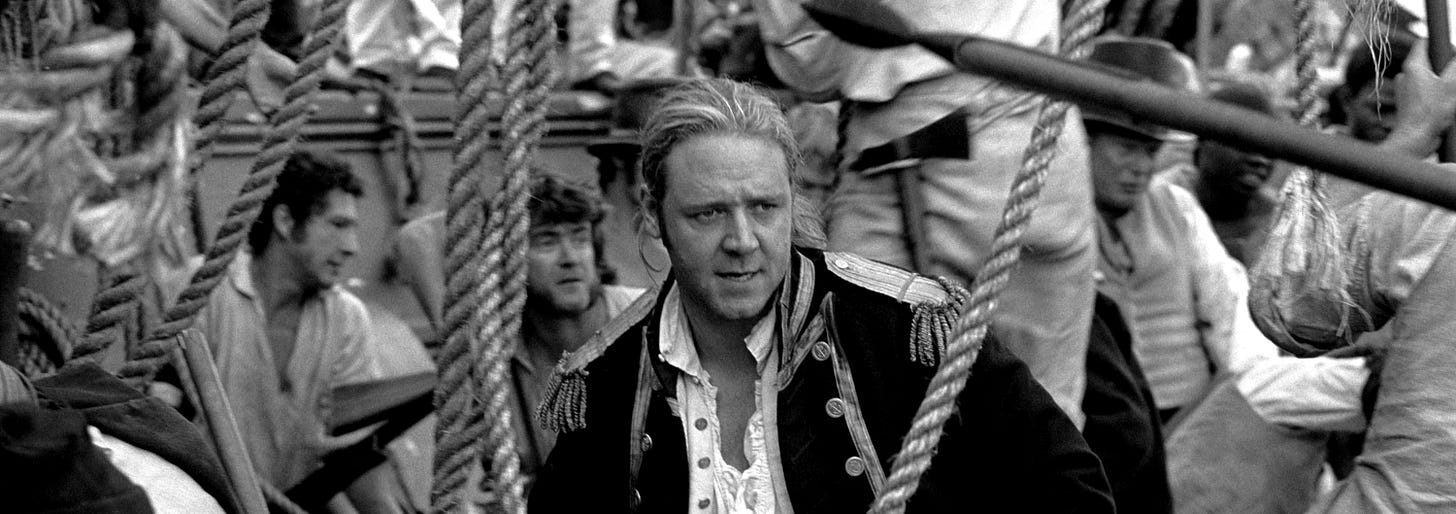

After reading Patrick O'Brian's Master and Commander, the first book in the Aubrey-Maturin series, and then watching the eponymous movie, I began daydreaming like Lockwood — but about life in the Royal Navy circa 1803. Not the shooting part but the part where they stand on a slick wooden deck in a heaving ocean hoping to get promoted to captain. We're talking about a life of humid and cramped quarters, estimating speed (with literal knots), keeping time (with a sand hourglass), spotting foes on the horizon, beating to quarters, unfurling any spare canvas to eke out an extra knot (and hoping the mainsail holds God willing!) all so that, at the critical moment, the ship can be in the right spot to deliver lumps of steel into an equally beautiful and deadly vessel, manned by Frenchmen, Spaniards or Americans.

O'Brian conveys these mechanics perfectly. You get to feel as if you actually know what losing a topmast means for a ship and what modified tactics are appropriate when engaging an opponent in a high swell, rather than a moderate one. We also feel how rank and discipline permeates every moment aboard, seeping into every conversation. Every sailor is at the mercy of it, every officer is obsessed with it, craving as they do nothing more than to command a ship of their own. Even the captain wants a bigger ship or the command of a squadron or a fleet.

This was one way I'd been imprinted, I was more disposed to authority and rank than ever before. This was not my usual look — I usually chafe under control and want to get from under it and I feel uncomfortable controlling others. But control seems to be an inherent part of seafaring. If you've ever been aboard a sailing boat with an experienced captain you'll quickly realise the extent of your own incompetence and the wisdom in deference. The simple struggle of staying afloat on a changeable and indifferent sea is hard enough as it is. Arguing over who gets to steer is dangerous. This makes the sea one of the few contexts where total control is justified.

And ships are an ideal environment to exercise control. The story of ships as prison is long and salty. The late middle ages saw convicts, debtors and prisoners of war used as galley slaves: losing their freedom, gaining large biceps and lats. Even today the one Italian word for prison is galera, which also means ship. In the late 17th century British prisoners were sent to prison hulks on the Thames, forced to dredge up the bottom sludge and silt of the river, day after day. Only two years ago we saw a 800-bed prison barge in New York finally decommissioned. Unfreedom and the ocean are deeply linked. Then, most relevant to our topic, we have impressment, a practice of conscription perfected during the age of sail by the Royal Navy to fill the ranks of their huge fleet. You can see how, when a good portion of your sailors are there against their will, you might be tempted to flog them every now and again.

So, this type of nautical novel, written from the perspective of a skilled and honest captain, is almost by definition pro authority.1 From the perspective of an able seaman you'd get an account of one dreary task after another. Something close to *One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich* on sea, punctuated by moments of terror. Instead we’re brought into the world of the responsible captain, the person who has to make all the right choices under constant scrutiny.2

In a climactic scene in Master and Commander, we watch the HMS Surprise and her crew sail east through the dreaded Drake Passage, in pursuit of a French vessel (in the book it was an American ship during the war of 1812, changed in the film for obvious reasons). They find themselves caught in a storm. After much fiddling about with the sails a seaman is tossed overboard along with a mast. The mast, still attached to the ship by a rope, makes the ship list perilously. There's still a chance to save the lone sailor, but it could mean the already embattled ship might be dragged down into the depths. The sailors' friends cut the rope and watch him, so far from green England, disappear into the storm. We understand that the collective is more important than this single man’s life. He is a sacrifice to his shipmates. Was his loss worth the pursuit of the French ship? Hard to say. We are invited to question Captain Aubrey's motivation for hazarding the passage: naked ambition, a sense of duty, love of country, has he simply gone insane? The question lurking behind the questions is simply: is he the right man for the job? That someone needs to be in absolute charge is never in question.

This brings us, inevitably, to the apocalypse narrative, which is frequently right wing coded. A typical story goes: after the initial chaos our protagonists find themselves in a state of relative safety. The world has ended but they’re okay, for now. Then they cross paths with someone in need: should they help the stranger or leave them to die? Usually they help. When they're inevitably betrayed they learn that the world has changed. Strangers prey on kind hearted naives. Eventually the heart grows cold and no more risks are run. See: Book of Eli, Walking Dead, The Last of Us.

I know this feeling all too well. Allow me to shift the scene from the 18th century Royal Navy to the heady days of my boyhood. One subarctic summer, on a short lived sailing course, I found myself placed on a rowboat with seven other children and a teenage instructor. Tasked with rowing around for a bit, we bobbed into the small bay, making slow progress against a strong wind and swell. At some point the teenage instructor handed control of the rudder to me — I was now captain. My spindly oarsmen heaved, I held the rudder as instructed (bow angled into the oncoming waves) but inexorably the shore drew nearer, the waves pushing us ever closer to land. The merciless waves and sky merged into one oppressive grey and we finally ran aground on a beach not too far from where Sky Lagoon is today. My shipmates were furious. My short and bitter captaincy was over, my nautical reputation in tatters.